Before I start this blog, I’d like to apologise in advance

– I had written 6 pages of wonderful rhetoric, filled with insightful points of

interest and fascinating observations... but then my computer deleted it.

As such, I’ve had to rewrite the entire thing, and as such it will be nowhere

near as effective – I watched the serial more than a week and a half ago, and

have since listened to the next two serials, as well as the series finale of

the reboot, so my memory is a little hazy, and my notes make little

sense. So, sorry.

And so we come to the end. Season 4, serial 2, sees

us bid a heartfelt farewell to the Doctor – Hartnell’s moving on, and

Troughton’s taking over the reins. But what a way to bow out – the

introduction of the Cybermen! The first ever regeneration! (Although of

course we don’t know that that is what it is just yet.) But after a long

and dedicated service to the character, Hartnell’s swansong is both wonderful

and a tragic shame.

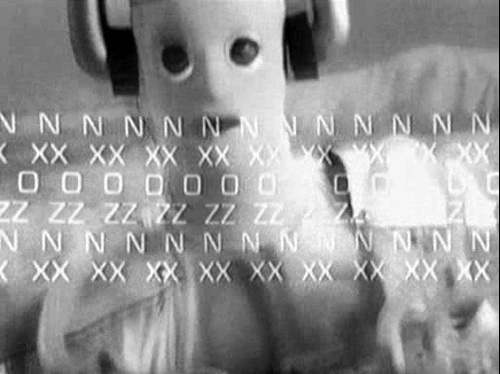

The Tenth Planet is regarded by many as the holy grail

of Doctor Who, and episode 4 is the most eagerly-sought episode to be

returned to the archives. It is a fantastic serial for any number of

reasons, and from the opening of episode 1, we can tell that this is something

special; the unique opening sequence lets us know that this is something

special, as computer scrawl fills the screen, gradually transforming into the

episode titles. The sequences in Snow Base are equally impressive, and

help to create a global sense of scale for the proceedings; as with The War

Machines with its use of news broadcasters and American journalists, we are

thrown into a world filled with people of every culture, albeit a number of

them are racial stereotypes – from the Italian opera-chanting lothario with the

sexy girl posters to the bullish brute of a General, barking orders in his

brisk American accent – and we can genuinely believe that there is a danger for

the whole planet, not just a suburb of London, as becomes the norm once Pertwee

takes over. Again, the use of stock footage here helps to create a sense

of scale, making it all the more believable. In a time of space

exploration, the shots of rockets must have seemed magnificent.

The arrival of the TARDIS is lovely too – the barren tundra

is wonderfully realised, and the materialistion is faultless. The

costumes, too, are noteworthy of praise, as Ben, Polly and the doctor step out

into a landscape as alien as any we’ve seen. Set in the not-too-distant

future of 1986, it allows the action to be carried by the performances, rather

than being distracted by space-age costumes. All of the characters are

dressed in such a way that we can tell where we are, both physically and

in a chronological sense.

Considering this is Hartnell’s swansong, and that he has

gradually been removed from serials as a focal point, he is on top-form here

again as always; his incredulous reaction to Cutler’s constant “pop”-calling is

magnificently delivered. In fact, all of the performances are top-notch,

as though the crew are aware that they are making history here. Craze, as

Ben, is his typical self, heroic, disgruntled yet respectable. Wills, as

Polly, is clearly loving being the only female on show, and plays her part with

a girlish glee which warms even the coldest heart.

Perhaps the best performances, though, come from the

astronauts, Williams and Shultz, on board the Zeus 4 shuttle, played by Earl

Cameron and Alan White respectively. Whilst the scenes in the cockpit of

the ship have a great potential to be hokey and boring, occurring as they do in

one small, claustrophobic space with no dynamic camera work, instead they

become riveting, and their performances gradually become more panic-laden as

they realise that the ship is slowly slipping from their control. Each

movement becomes a chore, and it is a true pleasure to watch.

The incidental music is superb, too – released on CD back

in 2000, it creates a genuinely palpable threat as the chords become heavier

and tenser, and accompany the visuals magically. The final scenes of the

first episode, as Mondas is revealed, are superb – again, the excellent model

work helps to sell the realism (although the planet is spinning far too quickly

upon its axis!) and as Hartnell warns of the impending “visitors” from this identical

planet, we get to see them approach through the snow, with twanging chords and

frantic pulsing sounds on the score. The appearance of the Cybermen is

fantastic, and is one of the best cliffhangers we’ve seen yet – the slow march

is something we’ll see again in The Wheel in Space and The Moonbase,

but for now it is original and fresh. The scene in which one of the

Cybermen swiftly deal with a scientist with a blow to the back of the head is

horrifically violent, particularly as the camera feels like it has lingered on

the shot just a moment too long before cutting away. Also wonderful is

the final scene, as the camera shows a close-up of the human hands of the

Cyberman, impervious to cold and utterly without feeling, as it shifts the

corpses uncaringly aside.

As with The War Machines before it, the use of news

reporters in episode 2 helps to create a sense of scale, as the world wonders

what on earth the new planet could mean. The sequences in Wigner’s office

at Geneva also help to sell this idea, as they desperately try to deal with the

situation. The presence of multi-national characters in non-speaking

parts furthers this idea.

In fact, much of the direction is wonderful – the scenes of

the Cybermen’s arrival are spectacular, and the framing of them with snow on

the camera lens is smashing. Likewise, the use of the panning shot across

the snow base as Barclay gives his speech is wonderful, showing each of the

actors with nuanced characteristics, paranoia and fear etched onto their faces.

The Cybermen themselves are quite magnificent – whilst they

are nowhere near as polished looking – pun intended – as they appear in Revenge

of the Cybermen, and certainly nothing like as chilling as in the newer

series with The Age of Steel, here, they are unnerving because they look

so temporary. Rather than perfect robots, identical and lacking any

identity, instead the aliens look like they have been assembled from spare

parts and junk. The cloth faces are horrifically devoid of all human characteristics,

and they tower over the crew of the polar base, chinks in their armour and

all. The speech patterns are the most horrifying thing about them,

though; the actors performing the Cybermen open their mouths at random

intervals whilst the voices, provided by the ever-reliable Roy Skelton and

Peter Hawkins, are played in. The modulation of the voices is terrifying

– “You call them E-e-emotions” – as emphasis is put on the wrong part of the

sentence, inflections fluctuating. With the appearance of the creatures,

mouth open and vacant eyes staring, it creates an horrific image of

alien-ness. Physically, the Cybermen are intimidating too, and not just

because of their height. Their sheer brute strength is displayed in a

show of power when one Cyberman takes a gun and bends it as though it were made

of rubber.

The claustrophobia of the shuttle scenes is swiftly cut

short, as Zeus Four explodes – and the lack of emotion of the Cybermen makes it

all the more horrifying, as they simply shrug it off as inevitable. Their

understanding of human emotions is terrifying, as they simply consider them to

be a “weakness.” Emotional power is quickly resumed, however, when the

bullish Cutler discovers that his own son is now on a suicide mission, sent by

his superiors on a pointless crusade. His inner turmoil leads to him

making a number of irrational choices, and allowing Ben to become the moral

centre of the story as he tries to defuse the situation, and the Z-Bomb

intended to be fired.

Episode 3 is my biggest bugbear though – not only is it the

last moving images of Hartnell we’ll see, he doesn’t even appear in it!

As his health rapidly deteriorated, he called into the office to inform the

crew that he was unfit to film episode 3, leading to swift rewrites. What

is incredible is that the previous serial, and the opening story of season 4, The

Smugglers, had been filmed as the last block of season 3. Hartnell

had voluntarily come in to film The Tenth Planet, despite his ailing

health, to provide closure for his portrayal of the character and to help usher

in Patrick Troughton’s Doctor. And really, he gets a raw deal of the

whole thing. After months of relegation, this serial should have been his

grand exit, his outstanding swansong. Whilst his illness was untimely but

unavoidable, even when he is on screen, he is vastly underused.

However, Hartnell’s loss was Craze’s gain, and Ben becomes

the key player in this episode, crawling through ventilation systems and saving

the day. After the Doctor collapses, he is ushered into the bedroom and

placed under the covers, unseen for the rest of the serial. Ben talks to

him endlessly, muttering in fact to himself about the situation, and again it

is a testimony to the power of Hartnell’s Doctor – even when unconscious, he is

there to provide guidance to the companions. The camera work in the

air-duct system is wonderfully handled, creating claustrophobic setting and a

genuine sense of danger. The incidental music is also wonderful, all

strings and drums, rattling away as the tension is ramped higher and

higher. Ben is able to get to the control room with the Z-Bomb, but is

swiftly dealt with by Cutler and his men, and we are left unsure whether his

sabotage has been successful as the countdown flickers across our screens.

Of course, the rocket fails to launch, and Ben has saved

the day. Cutler’s threat is horrifying, as he tells Ben that he’s doomed

for interfering with the launch, and of the Doctor, warns “he’s gonna get

worse.” The fourth episode sees both the Doctor and the Cybermen return

to the foreground after their absence for the most part of episode 3.

Sadly though, as mentioned earlier, this episode is missing, save for a few

poor-quality recordings made by fans who clearly knew that this was going to be

something special. In these brief clips, though, we can see just how

magnificent Hartnell still was – in the face of his illness, he still stands

tall against the Cybermen, with the power and disgust we have come to know and

love of this incarnation.

Of course, the rocket fails to launch, and Ben has saved

the day. Cutler’s threat is horrifying, as he tells Ben that he’s doomed

for interfering with the launch, and of the Doctor, warns “he’s gonna get

worse.” The fourth episode sees both the Doctor and the Cybermen return

to the foreground after their absence for the most part of episode 3.

Sadly though, as mentioned earlier, this episode is missing, save for a few

poor-quality recordings made by fans who clearly knew that this was going to be

something special. In these brief clips, though, we can see just how

magnificent Hartnell still was – in the face of his illness, he still stands

tall against the Cybermen, with the power and disgust we have come to know and

love of this incarnation.

The biggest threat to the Doctor and his companions,

though, seems to come in the form of Cutler, whose emotional state threatens

his sanity, and his desperation is what drives him to such acts; Robert Beatty

is magnificent in these scenes, as he fluctuates from his boorish self to an

emotionally-wrought man fuelled by paternal concern. It is this very

desperation which ultimately leads to his death – blinded by his concern for

his son, he fails to fully appreciate the danger within the base.

Polly is swiftly taken hostage by the Cybermen, ensuring

that Ben and the Doctor do as they are told, and the Doctor’s final comment to

her as she leaves – “Don’t forget your coat!” – reminds us of his grandfatherly

ways. The Doctor quickly realises the Cybermen’s plan, though, and as

such is also taken hostage – again, removing him from the main thrust of the

action to sit in a chair, where “this old body of mine is wearing a bit

thin”. Again, this foreshadows his final bow, once more removing him from

the crux of the action and instead allowing Ben to take centre stage and,

ultimately, to save the day. It is Ben who realises that, despite their

brute strength and metal exterior, the Cybermen are impervious to

radioactivity, and so the survivors use the radioactive rods to fell the

remaining invasion force as Mondas burns itself up and melts, taking all of the

Cybermen with it. Snowcap is able to resume radio contact with Terry

Cutler in space, and the Doctor and Polly are saved from the Cybermen’s ship.

The final scenes are unnerving, though – after all we’ve

seen of the Doctor over the last 3 and a half seasons, he returns to his

original form, crabby and unapproachable, and as he makes his way back into the

TARDIS, we are left believing, just for a moment, that he intends to leave Ben

and Polly in the South Pole. They manage to enter, though, and we witness

a transformation, as the creased, white-haired old man suddenly transforms in

an explosion of white light into a small, spritely looking fellow. The effects

are pretty flawless, and no explanation is given – after the Doctor’s collapse

and his weakness in the chair, we are given no reasoning (although it can be

presumed it was to do with Mondas, and there had originally been an explanation

in the first script) for the change. Hartnell’s last speech before this

transformation is in retort to Ben’s statement – “It’s all over? That’s

what you said – but it isn’t all over!” – and how right he is. The

adventures don’t stop with a change of image. The Doctor lives on…

These cybermen were just the first prototypes. They were just one of the first people converted during in their first test. The ones that came later were the

ReplyDeletereal ones, such as the ones from Tomb, which, for me, were scarier. Their voice was even more chilling. But see, I still think that the ones from Age of Steel were the scariest. Sure they didn't need to bring a new whole race, or make the story based on the "parallel world" but otherwise everything was so well planned, to show how the Cybermen return. The Cybermen themselves were really chilling. They looked like cold,empty, metal people whose real bodies are now ruined and they can never change back. Their empty black eyes and their stomping freaks me out. Their movements were so fast, and they looked tough. A cold emotionless civilisation. And they weren't so weak, they were the humans that have really help them escape death. People cannot just throw and kill them. But well, everyone has different opinions,of course, and I was just expressing mine here.

My grammar lol

Delete