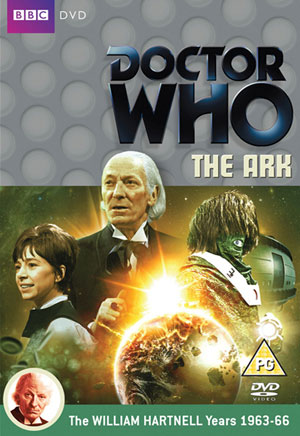

The Ark is a fascinating example of Doctor Who at its very

best. Essentially a warning against taking advantage of others, and the

ingrained xenophobia prevalent in much of society, it throws the audience from

the relative safety of the ‘known’ – the Historicals – and the unknown – the

sci-fi stories – by suggesting that all that we have seen has been within one

particular quadrant of time, and that, instead, we are being thrown into the 57th

segment of time. Whilst in the past it has been the purpose of the crew

to save the Earth from destruction and invasion, here we are asked to look at a

future in which the world has already been destroyed. The remaining

humans are travelling through space, in the Ark of the title (as named by Dodo)

and are searching for a new home upon which to settle. It is a theme

which was touched upon in Galaxy Four, and one which will be revisited

in numerous stories in the future, whether with humans, in stories like The

Ark in Space, or other alien species in tales like The Horns of Nimon.

The very nature of these nomadic people throws the audience, forcing us to

question exactly how we would react given the same situation.

From the opening of the serial, we are greeted by wonderful sets,

designed by Barry Newbery, which create a truly magnificent sense of scale. The jungle set is wonderful, and the cutting

between film and video is almost flawless.

Indeed, one of the strongest things about this particular serial is the

brilliant direction from newcomer Michael Imison. This is the only serial he directed, but it is

difficult to see why – he has a natural flair for interesting shots, making

great use of cranes and filming through sets to create a sense depth of field

which is rare in early Doctor Who. Imison is also responsible for the creation

of the Monoids as they appear in the finished show – it was his decision to

reimagine them as one-eyed monstrosities, and it was at his suggestion that

they used the ingenious concept of a ping-pong ball to create the moving eye.

What

is rather intriguing about this first serial is the character of Dodo, as

played with childish enthusiasm by Jackie Lane.

Dodo is far and away my least favourite companion of the first Doctor,

and one of my least favourite companions ever, and upon re-watching this

serial, and a couple since (I’m writing through a backlog of viewed stories due

to my accident last week)it is easy to see why I have such a disdain for

her. In the fantastic novelisation by

the serial’s author, Paul Erickson, Dodo’s character is granted a variety of

layers – and until the DVD was released, it was the only experience I’d had of

her original adventures. I’d seen her

briefly in The War Machines – very

briefly! – but neither The Ark nor The Gunfighters had been released, so

I’d not had the dubious pleasure of seeing Lane in action. To some extent, I wish that were still the

case. She’s just so dreadfully

irritating, constantly... But more on

that in later blogs. This is probably

her at her very best, not that that is saying much, mind.

From

her very first moments, she plays the part with doey-eyed excitement, bubbling

on (no longer with her non-specific accent from the week before) about being in

Whipsnade. Quite why she questions the

idea that the TARDIS really could travel through space and time – yet never

even questioned the ‘bigger-on-the-inside-ness of it all – grates on me. The fact that she has disappeared into the

bowels of the ship, to get changed into that most ridiculous costume, shows

that she hasn’t simply stepped in and then back out again at their new

destination, so some time must have passed.

Incidentally, the costume is rather an odd choice too – it had been said

that the idea for her character, originally at least, was to dress her up to

highlight the frivolous nature of her youth, with her excited by the prospect

of fancy dress. Unlike Ian, Barbara and

Susan though, back in The Reign of Terror,

the costume is preposterously out of place.

Purves does his very best at trying to calm her performance down, but

even he struggles to restrain her.

From

her very first moments, she plays the part with doey-eyed excitement, bubbling

on (no longer with her non-specific accent from the week before) about being in

Whipsnade. Quite why she questions the

idea that the TARDIS really could travel through space and time – yet never

even questioned the ‘bigger-on-the-inside-ness of it all – grates on me. The fact that she has disappeared into the

bowels of the ship, to get changed into that most ridiculous costume, shows

that she hasn’t simply stepped in and then back out again at their new

destination, so some time must have passed.

Incidentally, the costume is rather an odd choice too – it had been said

that the idea for her character, originally at least, was to dress her up to

highlight the frivolous nature of her youth, with her excited by the prospect

of fancy dress. Unlike Ian, Barbara and

Susan though, back in The Reign of Terror,

the costume is preposterously out of place.

Purves does his very best at trying to calm her performance down, but

even he struggles to restrain her.

The

Monoids lurking in the undergrowth is rather creepy, and even when I am aware

of their presence, the way in which they seemingly materialise is chilling. Through clever camera angles and intriguing

set design, they are utterly hidden, and the sheer number of them present still

sends chills down my spine. The opening

scenes are actually rather wonderful – the editing between the elephant and the

TARDIS crew looks utterly standard by Doctor

Who conventions, but the audience are thrown by the sudden interaction with

said elephant. Rather than what we have

come to expect – stock footage of animals interspersed – we are instead treated

to a moment of absolute pleasure as Hartnell, Purves and the irrepressible Lane

get to play with a baby elephant! It’s

magical, and again adds to the grand scale of the production.

The

scenes with the Guardians are rather chilling too – the last descendents of

mankind are portrayed as a bunch of dithering people, running their own form of

judicial service, and waited upon hand and foot by the Monoid slaves. The trial sequence in which we see them

handing out their brand of justice – miniaturisation – is unnerving, although

it does raise a strange point. The ship

on which these nomads travel will take 700 years to reach Refusis II, yet the

punishment is to be miniaturised for 700 years.

As such, the criminal Guardian being punished is being afforded a second

chance; a life on the new colony.

Meanwhile, those Guardians toiling on the travels will perish one by one

as the ship makes its journey towards their destination, preventing them from

ever seeing their future world.

The

scenes with the Guardians are rather chilling too – the last descendents of

mankind are portrayed as a bunch of dithering people, running their own form of

judicial service, and waited upon hand and foot by the Monoid slaves. The trial sequence in which we see them

handing out their brand of justice – miniaturisation – is unnerving, although

it does raise a strange point. The ship

on which these nomads travel will take 700 years to reach Refusis II, yet the

punishment is to be miniaturised for 700 years.

As such, the criminal Guardian being punished is being afforded a second

chance; a life on the new colony.

Meanwhile, those Guardians toiling on the travels will perish one by one

as the ship makes its journey towards their destination, preventing them from

ever seeing their future world.

Dodo’s

cold, a rather irritating little bit of characterisation at first, actually

turns out to be a central plot device, which is rather clever. The idea that the humans from the 57th

segment of time have lost their immunity to the virus is wonderful, and

provides a thrilling drive for the first two episodes, which at first glimpse

seem to be all there is to this story.

Unnervingly, the Guardians on the ship have a rather distasteful slant

on this – whilst Monoids suffer hugely, dropping like flies, it is only once

one of the humans die that anything is genuinely done about it. There is a very clever moment, whilst the

time travellers are locked up, that seemingly diagetic music during the

beautifully choreographed Monoid funeral procession is commented upon – Dodo

makes a flippant comment that it makes them sound like “savages”, despite the

honour evident throughout. The model

shot of the corpse being ejected into space is smashing too.

What

is odd about these scenes of the virus spreading is not how the humans and

Monoids are affected though – it is the fate of Steven. For some reason, when one of the TARDIS crew

is requested to represent them, it is he, rather than the Doctor, who steps to

the plate. Whilst Purves is given a

magnificent speech, spouting platitudes about xenophobia and how the humans

haven’t changed – "That the nature of man, even in this day and age,

hasn't altered at all. You still fear the unknown like everyone else before you"

– but then he too, inexplicably, succumbs to the illness working its way

through the crew.

...............except

they aren’t. This is the same jungle

set. We’ve been here before – only

moments ago, in fact. The serial manages

to knock the audience completely off balance with the simplest of devices, and

it is marvellous. Never before have we

seen the Doctor return to an exact location, and see the aftermath of his

actions. Imagine him returning to the

streets of Paris following The Massacre, the

pavements still slick with the blood of the Huguenots. Or back to Kembel years later, surrounding by

the ash of the fallen. But we still

don’t know why the TARDIS has decided to bring them back – until Dodo spots the

statue, previously only two severed feet, which has now been completed – but

with the head of a Monoid. So the Doctor and his crew rematerialise on the Ark

700 years later, and all of a sudden we realise that the Monoids weren’t simply

set-dressing – they were the integral part of the plot. All along, they were taken for granted by

everyone – with the slight exception of the Doctor who thanks one for his

service in the laboratory; and then we realise that we’ve taken them for granted too.

In

fact, as with Steven in The Massacre,

we realise that everything that happens is due to their interference, and

they’ve brought about the last hopes for humanity through their meddling and

spreading Dodo’s common cold. It is

suddenly essential that they interact, and somehow get things back on track –

it is their responsibility.

The

Monoids themselves work magnificently – with their single eye swivelling back

and forth, and the voices provided by the ever-brilliant Roy Skelton and the

able John Halstead, they embody magnificently the oppressed striving for their

own rights, and becoming megalomaniacal with the power available. The very idea that the virus drained the will

power of the humans is a nifty one – and through their lack of willpower, the

Monoids have risen to become dictators, using the remaining Guardians as their

own slaves.

Parallels

between World War Two and alien races are nothing new to Doctor Who – arguably best portrayed through the Daleks and their

similarities to the Nazis. Here, though,

Edmund Coulter’s portrayal of Monoid One, the leader of the Monoids, manages a

cleverly balanced performance, reminiscent of Adolf Hitler on the stands at

Nuremburg. His gestures, sweeping arm

movements and decisive chopping motions, become more and more erratic as the

serial continues, and there is a wonderful synergy between him and Skelton, off-screen

providing the voice. It’s a lovely, and

utterly justifiable, acting choice – a natural progression from the sign

language, seen earlier, continuing even after the creation of their voice

boxes.

Upon their discovery wandering the deserted ship, the Doctor and his crew are swiftly bundled off to the security kitchen – yes, really! – and kept prisoner. What is lovely about this scene is that just before their arrival, we get to see two of the human slaves, Manussa and Dassuk, discussing the Doctor, and referring to him as a legend, a fairy tale to keep up the spirits of the oppressed. In hindsight, it is a wonderful nod to the importance of the character, and one which is still as relevant today; indeed, it is this very notion which is used in the rebooted series of the show which proves to be the saving grace of the world in Last of the Time Lords and a title which proves to nearly be his downfall in The Pandorica Opens.

The

Refusian voice is provided by Richard Beale, delivered in rich and dulcet tones

creating a sense of presence and power, and as it tells of peace and tranquillity

it is easy to be absorbed by the exposition – and the destruction of the

launcher, with Two inside, is wonderful, as is the cliffhanger at the end of

the third episode, with the Doctor and Dodo stranded on Refusis II, with no

ship and no way of communicating.

The

fourth episode is sadly where things really start to fall apart – whilst the

direction remains clever and innovative, the plot begins to spiral, helped by

the costume design of the Monoids.

Whilst the faces and upper torsos are cleverly realised, looking alien

and menacing, the movements of the actors are somewhat inhibited by the fact

that their legs are practically bound together by the lower part of the outfit,

and they end up waddling rather comically.

As such, the Monoid rebellion loses the gravitas it deserves – the entire

motivation for the civil rebellion is that Four argues with One, and so almost

every Monoid is massacred. The resolution

of the storyline involving the double-cross of the humans is wound up far too

easily – the Monoids gloat about the bomb being inside the head of the statue,

and so the Doctor tells Steven and the remaining Guardians, and the statue is

disposed of. It all seems a little too

easy. It would have been nice to have

strung the resolution out a little further, particularly for the audience – had

we been kept in the dark a little longer it may have maintained some of the

dramatic impact.

In

fact, the scenes of the bomb being removed from the Ark, carried by a Refusian,

offers an interesting and puzzling thought – just how big are these

things? They are able to fit into the

Launcher, suggesting that they are no more than 7ft tall, and yet they have the

strength so that one of them can carry the vast statue, which must way hundreds,

if not thousands, of tonnes, and place it into the ejection bay! (Although the movement of the statue must

once again be praised – a simple effect, yet masterfully handled)

Following

the Monoid rebellion, and the removal of the bomb, we are treated to a lovely

speech by Hartnell, as he reminds them that “you must travel with understanding

as well as hope. You know, I once said that to one of your ancestors, a long

time ago.” The crew then depart, leaving

the humans and the Monoids to get along, under thee always watchful gaze of the

mighty Refusian.

The

episode ending dovetails nicely into next week’s serial, as the Doctor begins

to fade in and out of existence, and there is a genuinely palpable threat as we

are warned that, next week, we are entering “The Celestial Toyroom”.

Oh,

and Dodo’s outfit, a huge improvement, is the first time a miniskirt was ever seen on television. Just for the record...

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment