Rage is something

of an oddity within King’s bibliography, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was the first (chronological)

release by Richard Bachman, rather than King himself. King wrote for many years under the pseudonym

of Bachman, as it allowed him to publish a higher number of books each

year. He was also intrigued to see how

these releases would go down with the public.

Secondly, it is the only novel he ever released which is no longer

available. King himself removed it from

print, as it had been tied to a number of High School shootings and he didn’t

want his work to become synonymous with such.

Rage is, to all intents and

purposes, a non-book. Yet, some lucky

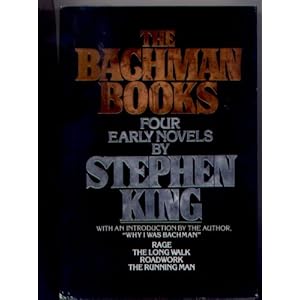

people (myself included) have copies, buried deep within the pages of The Bachman Books, a joint release of

this and 3 other stories published under the Bachman name. It is probably also available in some

libraries, and in a first-hand edition possibly circulating the likes of Ebay

and Amazon.

Rage is something

of an oddity within King’s bibliography, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was the first (chronological)

release by Richard Bachman, rather than King himself. King wrote for many years under the pseudonym

of Bachman, as it allowed him to publish a higher number of books each

year. He was also intrigued to see how

these releases would go down with the public.

Secondly, it is the only novel he ever released which is no longer

available. King himself removed it from

print, as it had been tied to a number of High School shootings and he didn’t

want his work to become synonymous with such.

Rage is, to all intents and

purposes, a non-book. Yet, some lucky

people (myself included) have copies, buried deep within the pages of The Bachman Books, a joint release of

this and 3 other stories published under the Bachman name. It is probably also available in some

libraries, and in a first-hand edition possibly circulating the likes of Ebay

and Amazon.

It is, by no means, a brilliant book. It is written in King’s typical style, but

minus some of his more inspired flairs which make his writing so great – as he

was writing under a pseudonym, the aim was to avoid making it too clear that

Bachman was King at all. It is funny,

then, that this novel sounds so much like him.

Whilst a number of other writers, Dean Koontz for one, try to emulate

King’s style, here, Bachman is King. It is difficult to believe that it took so

long for him to be found out, before killing him off with ‘cancer of the

pseudonym’.

The novella starts with Charlie Decker’s rambling direct

address to the reader, a first-person narrative which reminds us of Holden

Caulfield in Salinger’s Catcher in the

Rye. Decker is bright, achieves well

in school, and whilst not popular, seems to manage – he has had girlfriends, he

has a few close friends. He is a typical

high-school student. From the outset, we

know that he has issues – he imagines, on his way to the principal’s office,

his Math teacher chasing him, “hands raised into twisted claws” telling him

that they “don’t need boys of your type around here”. The first hint that Decker provides a threat

to his classmates and his teachers is as he reaches for the “pipe wrench that

was no longer there”. He is evidently

unbalanced, and as his imagination tells him, he should not be in a public school,

but an institute.

The scene in Mr Denver’s office is horribly tense – the principal

is trying to do his job, to care for the welfare of students. It becomes evident – although we are not yet

told the specifics – that Charlie Decker was involved in violence which

hospitalised a teacher. He has been

allowed back into school on the condition that he reports to a psychiatrist each

day – a fair condition, all things considered.

Yet Decker becomes a depraved monster, spouting guttural cruelties and

then partially undressing himself before emerging into the administrative

office accusing the man of rape. He is

subsequently expelled, effective immediately.

So he goes to clear out his locker, but instead tears up his text books,

sets fire to the contents of his locker, and calmly walks into his Math

classroom and shoots his teacher at point blank range, “spilling Algebra” all over

the floor.

Quickly, the school is evacuated, except Room 16, and the

hostage situation rolls out its course.

And this is where the book has its major failing. Whilst Decker is despicable, a rebel without

a cause committing two murders in cold blood and then holding his 25 classmates

hostage, he is written as an anti-hero, someone we are expected to identify with. But it is impossible to feel anything for

him. As he tells his tales of woe to his

rapt hostages, of his abusive father, of his bullying because he once wore a

suit to a children’s birthday party, of his failed sexual exploit, and of his

attack on his Chemistry teacher with the aforementioned pipe wrench, it is

impossible to side with him. His father

was a prick, a nasty man who beat him – but he deserved it. At the age of four, for “something to do”, he

destroyed every window of his own house to kill the boredom. It is right

that he was hit by his father. When

he tells us of the birthday party at which he got into a fight, one almost

feels pity for him – and then he fights back and calls the woman who arranged

the party a “fat old bag”, losing all sympathy.

Sure, he couldn’t get a hard-on during sex – but it would have been an

illegitimate affair, and he was off his face on pot. So no sympathy there. And as for the pipe-wrench incident – it is

inexcusable. The fact that he had a pipe

wrench in his pocket at all is a sign that he was unhinged anyhow; that he uses

it to smash the face of a teacher because he “baited” him, calling him up to

answer a question on the board, is preposterous. Decker is a bastard, a horrible, unstable, malicious

child who looks for sympathy from the reader, but shouldn’t get it as it

undeserved.

But the failing of this book is that he does get sympathy. During

this “circle jerk” of self-pity, all of the children, bar one, side with

him. They have just witnessed two

murders – executions, even – yet cheer for him, tell him it isn’t his

fault. They all sympathise with him, as

they each have their own cross to bear – Pig Pen’s mother is tight-fisted and

won’t buy him new clothes, but will spend money on shitty pencils. Sandra’s sex life is terrible, and her first

sexual experience was with Ted, the boy who won’t join in these

discussions. She regales of how it was

quick, it didn’t hurt, and she didn’t enjoy it; she then goes on to tell us

that she then tried to have a one-night stand in a car park to “feel something”,

and orgasmed without the stranger even “getting it in”. That these children can see something of

themselves in Decker is horrifying – Stockholm Syndrome is proven to happen in

hostage situations, where the hostages fall in love with the criminals,

understanding their case and siding with them due to the conditions and

situation the find themselves in. But

here, in a matter of two hours, 24 children are jeering and cajoling along with

the boy with the gun. It isn’t

believable.

After four hours, it is agreed that they will be released,

and Decker tries to bring about his own death at the hands of a police

officer. However, before this happens,

the entire scenario descends into a modern Lord

of the Flies, as the children gang up on the outsider, Ted Jones, the boy

who refused to partake in the “nasty little masturbation fantasy” of Decker’s

making. He is beaten, has ink thrown in

his face and hair, is bitten and has a high heel forced through his foot,

making “something crunch”. This

group-consciousness created by Decker’s hate has led to an act of disgusting

degradation, as each of the children has begun to stoop to his level – not to

commit murder, but to physically assault someone for ‘being different’. Their empathy with his story has caused them

all to devolve into a grotesque caricature of evil themselves.

Ultimately, then, Rage

is unlikeable for the very reason that it effective. Whilst King’s fiction is predominantly

focussed upon the idea that we are all good people with the potential for evil,

and that it is the act of not committing atrocities that defines us, here,

writing as Bachman, he eschews that moral standpoint for a scene of horrific

value – that children could possibly all commit

these acts, but they need a ringleader to provoke what they crave. As charismatic as Charlie Decker may seem, I

simply cannot believe him, as a character, and that he has the potential in him

to provoke such acts.

No comments:

Post a Comment